|

At first glance, it’s easier to compare Light Fall to other games than to see what sets it apart. Its gameplay, level design, and visuals owe a lot from both Super Meat Boy and Ori and the Blind Forest. But once you get into it, Light Fall is much more interesting for how it forges its own path than for how it sticks to any formula.

Light Fall is a hardcore platformer, challenging you to traverse its levels while dodging spike-lined corridors, lasers, and the occasional enemy. It has plenty of difficult moments, but it’s much easier and more accessible than the games that defined that genre, or even recent entries such as Celeste. Light Fall’s stand-out feature is a set of abilities based on conjuring boxes. For reasons explained early in the game, you’re able to place cubes that hang in mid-air below you or beside you, launch them to damage enemies, or remote control them for a few clever puzzles. You can then use them as platforms or wall-jump off their sides to navigate the game’s environments. These abilities introduce a welcome twist to the genre, and I was impressed by how easy they are to use. You’re often dashing at Sonic-like speeds through levels, and if these abilities were implemented awkwardly, they could have easily dragged the game to a halt as you tried to position boxes correctly. Fortunately, the developers clearly put a lot of work into making sure they feel just right. If you’re hurtling through the air when you summon a box below you, it’ll appear just far enough ahead to ensure you land on it. If you’re falling and create a box beside you to grab onto, it takes your trajectory into account, placing it at just the right height for you to stick the landing. At first, I felt like the game’s speed would become uncontrollable, but within a few levels, I had adjusted to its breakneck pace. Once you’re in tune with it, you’ll be bouncing from block to block as you scale to otherwise impossible heights or catch yourself from a lethal fall. Even aside from this mechanical difference, Light Fall plays much differently from the more punishing hardcore platformers such as Super Meat Boy. Where that game is all about finding the safest route through its deathtrap levels and pulling off perfect inputs, Light Fall is about using the tools at your disposal creatively and recovering from errors. If you misjudge a jump, for example, you can summon a box to land on and get a second chance. But your power isn’t a get out of jail free card. Once you jump into the air, you can only use your power four times before touching solid ground again (landing on your own boxes doesn’t count). The challenge becomes about finding the right time to use your powers as you leap through tight caverns full of deadly crystals. Deciding exactly when and where to place these platforms to get the most distance out of each jump means the difference between life and death. Stages often cram you into tight, winding corridors that force you into a more deliberate pace, while others allow you to just zip through the sky on a bridge of summoned boxes. They don’t always lean into the acrobatic freedom that your powers enable, but they’re still immensely satisfying. I had dozens of moments of breathless excitement as levels demanded nearly flawless sequences of split-second decisions to survive. You’ll often use your powers to catch yourself just before falling to your death or carve a winding path through brambles of instantly fatal obstacles. Unfortunately, it feels like Light Fall ends before it really explores all the possibilities of its premise. Its dozen stages can be completed in just a handful of hours, culminating in an extremely lackluster final boss fight. The game is absolutely designed to be replayed, however. It includes a speed run mode where you try to top your own best times and climb a leaderboard, and each level is packed with collectibles that you’re highly unlikely to find on your first playthrough. I had a good time going back through these modes, but they’re not quite as thrilling as making your way through the game for the first time. Light Fall puts an odd amount of emphasis on the story for a platformer of its type. You’re guided through the game by a narrating owl with his own ties to the world’s history. I found it all pretty skippable, to be honest. There’s nothing particularly bad about it, it just doesn’t do much to earn the forefront position it gets. The game’s music was similarly middle of the road. Its tone is wildly different from stage to stage, swinging from strangely somber tracks to casual, loungey beats. As far as presentation goes, art is the standout. Each of the game’s stages has a gorgeous backdrop painted with a neon color palette. I was ultimately left wanting more from Light Fall, which I suppose is halfway between a complaint and a compliment. I had a blast performing in its precision dance across platforms that I built as I ran. It struck the right balance between being challenging and never stalling progress, but came to an ended much earlier than I expected. The game’s core mechanic is interesting, but it rarely feels like it’s used to its fullest. All in all, Light Fall is a brief but inventive revitalization of a staid genre.

0 Comments

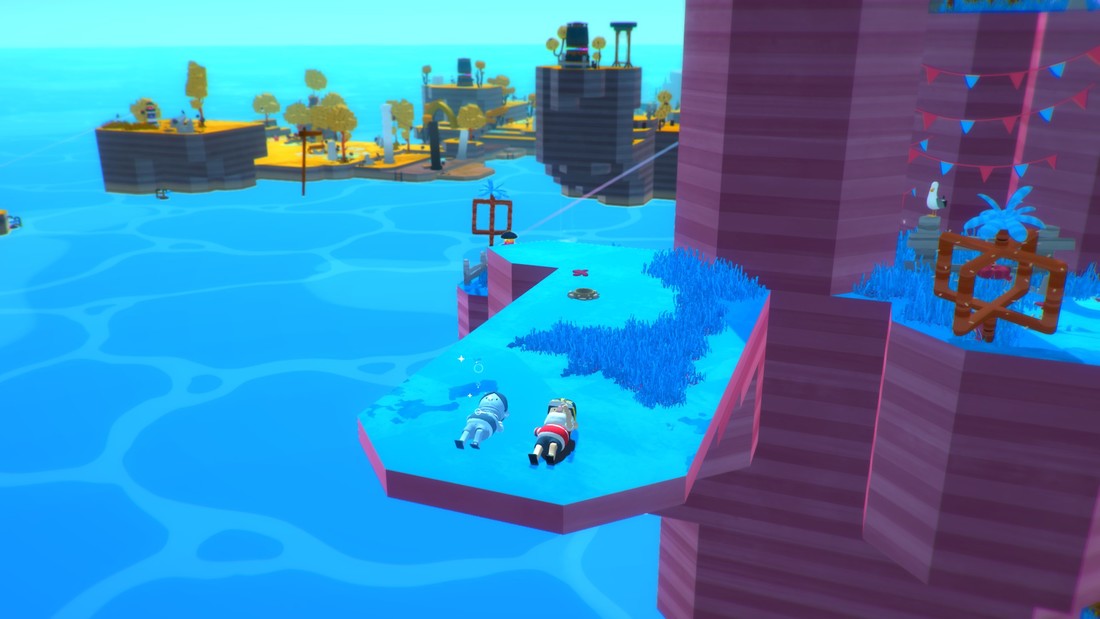

From the outset, Solo makes it clear that it’s not a typical game. It starts with three questions: What is your gender, how would you like to be represented, and how would you like your love to be represented? Soon you’ll be asked another question: What role does love play in your life? These simple, direct questions immediately establish a tone (achingly sincere) that persists throughout the rest of the game and forms the basis of your interaction with it. Choosing to present yourself as coupled, single, or heartbroken influences what questions you’ll be asked later, and perhaps more importantly, gets you thinking about your love life. This mindset will be crucial to your experience of Solo. Taken at face value, it seems to be a simple puzzle game. Traveling across a multi-color archipelago, you manipulate blocks and hang-glide through the air to reach tiny lighthouse-like structures. These activate larger totems, which in turn pose questions to you. We’re trained by puzzle games to see this endpoint as just a marker, a stand-in for achievement, and to see the block-pushing as the real point of the game. But Solo inverts that relationship. The goal here is to reach those totems, not because they signify that you’ve solved a puzzle, but because that’s where the real game is. The puzzles, and to some extent the totems themselves, stand in the way of your true goal, which is self-knowledge. The puzzles themselves are simple, but mostly excellent. You can pick up and move blocks, or float them through the air with a magic wand, to create a path to the lighthouses and totems. Picking up blocks with the magic wand feels great (and very similar to the magnesis power in Breath of the WIld). The controls are silky smooth and responsive; just navigating the island feels fun. Some blocks have special properties, such as fans that blow other blocks into the air or suction cups that grab onto surfaces, and you can combine these in different ways to reach your goals. According to the developers, puzzles don’t have set solutions, instead allowing you to make your own path to your goal. This fluidity occasionally got irritating when the environment provided no clear hint to a puzzle’s solution. But for the most part, I enjoyed it. The most difficult puzzles in the game actually became the least satisfying in a way, because the more time you spend working out their solutions, the less time you’re spending immersed in the game’s theme. Solo is not a game about puzzles. Solo is a game about love, and it’s not shy about saying so. Even the blocks can be read as symbols of the game’s themes of uplift, connection, and reaching out. In addition to the guileless totems flat-out asking you questions, the islands are also inhabited by a second set of beings who occasionally swing by to wax philosophical about the concepts you’re delving into. These spirits are much more lyrical than the inquisitive totems, and I found them somewhat less effective. Their monologues verge on saccharine, and they slightly contradict the idea that you’re shaping your own experience by setting their own tone for you. That said, they do set that tone well, even if they come off a bit melodramatic. From time to time, you’ll also encounter the manifestation of love that you picked at the beginning of the game. You can have light interactions with them, such as sharing a bench or helping them lower a drawbridge. They’ll often pop up shortly after you’ve answered a totem’s question to offer commentary on your choice. Sometimes their rhetorical questions come off as a little accusatory, but they’re never confrontational. They’re clearly meant to make you look deeper into your views and examine any blind spots or consequences of them that you may have missed. At times, their commentary felt slightly off the mark, imbuing my answers with meanings I didn’t intend but they generally had cogent things to say. It’s best to look at them as offering one outside perspective, rather than sitting in judgment or stating an absolute truth. I found them to be the most interesting of the “characters” that inhabit Solo’s world. And even if you don’t like what they have to say, it’s still nice to pass a few minutes sitting on a swing with them, taking in the view. Solo does these little moments extremely well. You have access to a guitar that you can play to make affect the weather or drain the world of color, seemingly for no reason than the fun of it. The islands are dotted with roly-poly dogs, jumping fish, and hungry moles. Some of these animals let you pet them, some beg for food, and others will flock to you if you play a nice tune on your guitar. You can also tackle a series of side puzzles (building paths for stranded dogs or diverting water to a dry garden) that are completely optional, granting no advantage toward actually completing the game. The world is so inviting, and its inhabitants so charming, that I was happy to while my time away solving these optional puzzles or just running around the island, catching wind drafts, and petting animals. Even aside from any goals, the islands of Solo just feel like places you want to explore. The graphics are almost overwhelmingly cute, and everything on the island looks soft and round and safe. It works with a huge color palette, painting its world in vibrant shades in a cartoonish, almost paint-by-numbers style. The music, on the other hand, is surprisingly melancholic, inspiring the introspective mood that is a prerequisite for getting the most out of the game. To say that Solo is a game like no other is almost selling it short. Its strange fusion of puzzle game and psychological inventory managed to pull off things that I didn’t know games could even attempt. For days after I finished it, I felt its after effects rumbling around inside me. You can take that as a kind of warning; if you’re prone to rumination and unhappy with your love life, Solo might bring you to some pretty dark places. Above all, the game is defined by what you bring to it. If you’re the type to call games with something to say pretentious, that’s probably what you’ll call this one. If you’re not willing to take a slow pace and do some soul-searching, you’ll find it boring. But if you approach Solo on its own terms and open yourself up to its curious gaze, you’ll find a unique experience that may just bring some hidden parts of yourself into the light.  Dead in Vinland starts strong with a gorgeous hand-drawn cutscene that quickly establishes the stakes. You essentially play as an entire Norse family forced to escape by sea from marauders burning your home for unknown reasons. Yet the gods are evidently as angry with you as your countrymen, and a storm grounds you on a mysterious island with few supplies. From there, each day is divided into two action rounds and a rest round each night. During the two daytime turns, you assign your family members to activities, such as harvesting, scavenging, or exploring. You can also upgrade your workstations or craft new ones to open up more complex tasks, such as hunting or farming. These workstations and the camp they inhabit are presented sort of like dioramas, with the camp itself spread across several horizontally arranged screens. Everything from the characters to the buildings has an attractive hand-drawn look that helps sell the story as somewhere between graphic novel and storybook. Within the first few rounds, you’ll come across a band of generic evil Vikings led by a staggeringly poorly written maniac, which introduces another dominant mechanic. Each week or so, this gang will demand tribute, in the form of one of your precious resources. This provides a good sense of short-term goals, as well as a few for the longer term: recruit allies and defeat the madman. It’s a standard setup for the survival sim genre, but the settlement building’s quirks started to open a rift between the game’s systems and its narrative that would eventually grow into a chasm. For instance, one of the structures you can build is a rest area. Napping there during the day will help your characters recover fatigue. Oddly, though, it recovers more fatigue than simply napping in the seemingly much more comfortable shelter you already have. You also need to build a cooking stove to roast meat, despite the fact that you already have a campfire from the start of the game. If you can look past the absurdity of some of its premises, the settlement layer of the game is engaging. There’s a wide variety of resources to collect and activities to undertake, making it possible to tailor your camp to accomplish your objectives in a lot of different ways. Your characters’ needs are as varied as the ways to satisfy them, making it necessary to plan several steps ahead and anticipate shortfalls before they become catastrophic. Dead in Vinland takes care to acquaint you with its mechanics much more than most survival sims, which I appreciated since unknowing missteps could ruin your playthrough down the line. If a single one of your characters’ meters (fatigue, hunger, sickness, disease, injury, and depression) reaches 100%, it’s game over. The tutorial shows you how to manage these meters and shows you the basics of building up your base, assigning tasks to your party, and exploring the island. However, constant interruptions for long conversations between your party members bog it down and make the information it gives you harder to retain. As for the dialogue itself, it’s the source of most of my frustrations with the game. Each of the four family members is a broad, uninteresting caricature. Eirik is the stoic father who blames himself for the family’s misfortune. Blodeuwedd is the equally stoic mother whose entire character revolves around her status as a mother and wife. Moira, Blodeuwedd’s sister, is a mischievous witch who is weirdly obsessed with her sister’s sex life. Kari is the rebellious daughter of Eirik and Blodeuwedd who would look more natural in Hot Topic clothing than a Viking’s garb. Watching these characters interact is insufferable, and when they do speak, it’s always with twice as many lines as they need. Their conversations are also packed with ellipses to indicate pauses and internal asides, each of which adds another full-screen card that you have to click through one by one. It’s honestly exhausting, but you likely won’t be tempted to read through any of them because the dialogue is terrible, packed with modern slang and repetitive jokes. Even worse, these conversations are often just setups to make life harder for your family. While some conversations result in the bond between characters strengthening, the result is more often detrimental. Either characters have a wedge drawn between them, or they gain points in one of their status meters. That would be fine if you could draw a straight line from your actions to their consequences, but it’s usually unclear why your actions had any effect at all. Rather than trying to roleplay any of the characters, I had to calibrate my dialogue responses toward what seemed like the most innocuous thing I could possibly say. Even then, the character’s actual statement would sometimes take on a different shade of meaning than I had intended and hurt them anyway. A lot of times you’re not even given a choice in the matter. Characters will just carry on their own conversations, with no input whatsoever, and end up harming themselves or each other. In a game where you frequently occupy a razor-thin margin between life and death, these scenes could end your game with absolutely nothing you can do about it. In some instances, you come across others on the island. Despite the game ostensibly taking place in Vinland (the Norse term for North America circa 1000 BCE), the island seems to be populated by more lost intercontinental travelers than aboriginal people. When you stumble upon another wanderer, you’re given a choice of which character to send as an envoy. In the first few encounters, I chose based on who I thought would make the most narrative sense: Send the mystic to deal with supernatural matters, and the patriarch to talk to a traveling priest. When their dialogue seemed a little canned, I reloaded to try the conversations with other characters, and saw the exact same words, just coming out of different mouths. I can’t say for sure that there are no unique encounters to find this way, but I was too disillusioned to put much thought into them ever again. Of course, not all of your encounters will be friendly. If you choose to send a character exploring, you’ll sometimes run across other islanders fighting to survive, namely by killing you and stealing all your stuff. As in so many games, dealing with your problems using violence is more fun than using words. When Dead in Vinland’s turn-based combat kicks off, each side’s fighters line up in a melee row and a ranged row. These rows affect which attacks you can use, as well as which targets these attacks can hit, much like in Darkest Dungeon. Each character’s stats determine their turn order and give them a number of action points they can use to execute attacks. Oddly, your characters seem to be placed into these rows at the start of combat randomly, so you often use your first turn getting them where you want them. Changing rows only takes one action point, and some moves throw in a row shift for free, so you don’t have to completely waste your turn on positioning. Combat was probably the most fun part for me, though it’s treated like a hazard to avoid while exploring and it eventually gets as tedious as the rest of the game. Classes have clear-cut roles in battle, and no one feels entirely useless, though some are naturally more powerful than others. Status effects are also emphasized in combat, enabling a lot more strategy than just picking the attack that does the most damage. Abilities are also pretty varied within individual characters, so I never felt like I was left with nothing to do in a turn. Although if you end your turn with unspent action points, you get one extra on the next round, which makes doing nothing sometimes the right choice. Winning a fight rewards you pretty handsomely, but it also leaves you open to taking lasting injuries. It strikes a good balance between risk and reward, and connects the combat to the survival sim in a way that games with multiple layers don’t always do. If you’re a fan of survival sims and aren’t bothered by cringe-inducing dialogue, Dead in Vinland is worth a try. The settlement management was actually quite good, but it was so peppered with inconsistencies and agency-stealing sequences that I couldn’t get as invested in it as I wanted to. I found myself hoping for bandit attacks just to break up the monotony. What frustrates me most is that its biggest weaknesses could be ripped out entirely without affecting the underlying game at all. It went further than most survival sims to tell a story and flesh out its characters, which I respect, but nearly every step it took in those directions was faltering. I can’t care about characters just because I’m in control of their fate, nor can I take a story seriously when it constantly breaks its own tone. It’s not that Dead in Vinland is lacking in any major way, it’s just a good game buried under a mountain of little annoyances.  Masters of Anima is a strange beast. Part RTS, part action game, it casts you as a Shaper, molding raw life force (Anima) into the form of Guardians (creepy soulless puppets who kill at your command). In gameplay terms, that means you control your avatar from a top-down perspective while also summoning and giving orders to a battalion of the aforementioned murder puppets. It’s a compelling concept that feels great when it works, but it sometimes proves too much to handle. After an animatic intro sequence narrated by Scottish Morgan Freeman, the game bombards you with its jargon-packed, emotionally shallow narrative. You’ll learn about Shapers, Anima, and Guardians, plus Builders, Golems, the Heartshield and Spark, and eventually Sunder Lords. Basically, a lot of extraneously capitalized nonsense that gives your character motivation. It doesn’t come into play much until the very end, until it’s hilariously thrust back at you in the game’s final minutes, as if you were interested in the mumbo jumbo that it treats as a revelation. You’re also introduced to your character, Otto, and his fiancee, Ana, both of whom are well acted if not particularly interesting. Ana is set up to be a much more powerful Shaper than Otto (the Supreme Shaper, in fact), which doesn’t turn out to mean much because she’s immediately captured by Zahr, the game’s red-eyed, black-robed, villain caricature. Zahr “Sunders” Ana, separating her into three parts, thus establishing Masters of Anima’s extremely video gamey plot. It feels like the script was sent through a time machine from 1998, both in how contrived it is, and in how gross it is to turn a supposedly competent female character into a literal object (or three) for the male hero to collect. It’s also completely irrelevant to the player’s motivation, which is of course that commanding an army of killer homunculi sounds like fun. There are a lot of mechanics at play in Masters of Anima, and the game does a decent job of introducing them without overloading you or holding your hand too much. Within the first level, you’ll learn how to summon, command, and destroy your first type of Guardian, and learn about the resources that doing so revolves around. Summoning troops uses Anima, which you find scattered around the environment, and destroying them returns that Anima to you. Not long into the game, you also learn how to summon a type of Guardian that leeches Anima from enemies, which becomes invaluable in battle. You quickly learn the finer points of controlling Guardians, which is mostly selecting them and clicking on enemies that you want dead or objects you want fiddled with. Issuing commands is easy; the trouble comes, oddly enough, from selecting troops. When you scroll through your troops (using shoulder buttons or your mouse wheel), you automatically select all units of whatever type you highlight. Issue a command, and they all move at once, but they’re then deselected. The options menu lets you decide whether to automatically select the next unit type in your list or to stay with the current unit type, but you have to push another button to call these troops back to you before you can give them another command. It’s a small quirk, but it left me constantly unsure of which troops I had selected. It’s also one quirk among many. A splash screen recommends using a game pad, but I found the keyboard and mouse much easier to use. With a game pad, you use a reticle that extends a short distance from Otto in the direction he’s facing to select individual units or small groups. From there you order them to move or attack. There’s no way to move the reticle aside from repositioning your character; an especially odd choice given that the right stick, which seems perfect for this, is instead only used to perform a dodge roll. This drastically slows down your ability to give orders, and turns your character into little more than a cursor chasing down your other troops and pivoting toward enemies to issue attack orders. With a keyboard and mouse, you use your mouse exactly as you would expect, clicking and dragging to select troops, then clicking enemies to attack. Later battles that involve moving subsets of units to engage new enemy waves or avoid area of effect attacks are a complete mess if you’re using a controller, but much more manageable with a mouse. Positioning is the key to combat, which makes this precision crucial. Combat takes place within designated arenas throughout the level, which I found disappointing, but it works well enough once you get used to it. There are really no minor enemies in the game; each time you encounter a Golem, it’s a real battle. Golems have massive health bars, along with a special bar that constantly counts down. When it hits zero, your enemy gains stronger attacks and starts to unleash area of effect damage across the battlefield. Around the midpoint of the game, combat started to feel like a slog, and I was just tossing wave after wave of Guardians at the enemies. That “strategy” works a lot of the time, but once I took a step back and committed to playing to the Guardians’ different strengths; combat became a lot more fun. You quickly add Guardians to your repertoire throughout the first few levels, ending up with five types. Protectors, your first allies, are your front-line soldiers, absorbing blows with their shields while bashing enemies with axes. Sentinels do lots of damage with their bows. Keepers drain Anima from enemies. Commanders boost nearby Guardians’ power. And Summoners create even smaller melee drones to send at the enemy. Each also has a special ability that you can activate by using Otto’s “Battlecry” at the cost of Anima. When you use this ability, it triggers a number of Guardians near Otto, which you can increase as you level up. For instance, Protectors stun nearby enemies, Keepers give you health instead of Anima for a short time, while Commanders relay your Battlecry, triggering nearby troops to activate their abilities in turn. Clustering your Guardians and picking the right time and place to activate your Battlecry becomes extremely important later in the game. Bosses were generally showstoppers, calling on you to use your Guardians’ strengths to the fullest to guide your enemy’s attention while attacking objectives elsewhere or finding safe spots from which to rain down damage on them. One late-game boss in particular tests your coordination by unleashing devastating area of effect attacks while summoning resilient Golems, demanding that you pay attention to a dozen parts of the battle lest you lose your entire army in one swoop. Unfortunately, your troops don’t always want to cooperate. Protectors, in particular, often seemed like lost lambs. Being melee fighters, they’re prone to getting tossed around, and can’t attack at range. I often found them standing motionless on some far-flung part of the battlefield waiting for me to tell them what to do next. It wasn’t uncommon to hit the recall button and eventually be swarmed by stragglers whom I’d apparently abandoned much earlier in the level. When you’re not ordering hundreds of automatons to their deaths, you’ll use them to solve puzzles. I kind of hesitate to even call them that, as you’re mainly just using your Guardians to traverse the environment. You’ll have Protectors push blocks and Keepers create shields that protect you from environments that have been corrupted by Zahr’s nefarious and poorly developed scheme. Given the extremely low challenge that these obstacles present, I often found them to be little more than irritating ways to slow down progress. Masters of Anima’s graphics and sound are nothing to get excited about, but they’re perfectly serviceable. The Guardian’s designs are varied and pretty interesting, and everything is rendered in a nice storybook style. I honestly can’t remember a single song from the game, but the voice acting lent the characters a lot of charm, despite them having about as depth as the cast of G.I. Joe. All in all, Masters of Anima is built around the strength of one great idea that it executes with mixed success. At its best, when you’re deftly maneuvering your troops to avoid attacks, using Protectors to tie up melee attackers while bombarding high-damage foes from afar with Sentinels and Summoners, playing the game felt the way that I always wanted Diablo’s Necromancers to feel. It’s an uneven game that falters often, but it left me wanting more. It seems like a case where a more sure-footed sequel would take its excellent premise and turn it into something much more impressive than its middling first attempt.  When you hear the word “cyberpunk” do you think of glittering neon cityscapes speckled with flying cars and populated by sleek androids? If so, Shadowrun would like to have a word with you. Old-school cyberpunk was about people who have been stepped on or stamped out by corporate-controlled technology in the near future, and how they used that same technology to fight back. The Shadowrun setting, originally appearing in 1989 as a pen-and-paper RPG, has always been a unique beast, mixing even parts fantasy and sci-fi. While the image of an elf hacking a computer to steal from a dragon is too silly for some to stomach (William Gibson, whose novel Neuromancer inspired Shadowrun, famously despises the games), the series offers a compelling peek into a technobabble-drenched life of crime. Harebrained Schemes released three Shadowrun games in the 2010s, and as far as I’m concerned, Shadowrun: Dragonfall is the best of them. Technically, we’re talking about Shadowrun: Dragonfall - Director’s Cut, which added a few new missions as well as an improved interface and other enhancements, but that’s just too much punctuation for one title. It’s also the only version of the game currently available. Set in the anarchic “Flux State” of Berlin in 2054, it expanded on the somewhat threadbare Shadowrun Returns without succumbing to the bloat that sometimes plagues its successor, Shadowrun: Hong Kong, which is still an excellent game in its own right. After stumbling upon a terrifying secret, you end up on the hit list of a group that could potentially destroy all of Berlin. Your mission is to shut the group down before they can take you out, though you spend most of the game running side jobs to earn the cash for this massive undertaking. Like the other entries in the series, Dragonfall is a turn-based strategy/RPG hybrid that mixes isometric grid-based combat with exploration and a huge amount of both character development and stat crunching. You play a custom character who takes control of their own squad of shadowrunners early in the game. Shadowrunners are essentially freelance criminals who are contracted for jobs as part of the neverending corporate wars that define the Shadowrun universe. In fitting with the game’s theme, you’re driven by the need for cash, not loyalty, and your employers have as much disdain for you as you do for them. When you go on missions, you can choose up to three companions either from your regular team who will grow alongside you, or from a pool of mercenaries if you’re afraid of commitment and also want to miss out on the best part of the game. The biggest advantage that Dragonfall has over the rest of the franchise is its characters. Despite my borderline unhealthy crush on Hong Kong’s rat shaman, Gobbet, your regular crew in Dragonfall comprises some of my favorite video game characters ever. Off the top of my head, nothing else even comes close. When you’re not on a job, you’ll spend your time in the Kreuzbasar, a relatively safe and stable neighborhood full of colorful inhabitants. Almost no one feels generic. Everyone from quest givers to simple shopkeepers has a distinct personality, even if your interactions with them are purely commercial. I found myself holding personal grudges against characters who had wronged me, and feeling something akin to friendship to those who managed to show kindness in the face of Berlin’s oppressive squalor. Of course, you’ll spend most of your time with your crew, which includes a disgraced commando (probably your least interesting teammate except as a foil to the others), a punk-singer-turned-shaman, and a young woman who’s replaced nearly every part of herself with machinery. They’ve all been chewed up and spat out by society in some way or another, either by supernatural forces, human supremacists, or the ruthless corporations that run the world. If Deus Ex’s Adam Jensen existed in the Shadowrun universe, he’d be just another prick standing between you and a paycheck. You can dive deep into your team members’ backstories as you play the game, provided you win their trust, and each not only fleshes out the game’s world and themes, but also stands as a fully realized person. Winning the trust of your allies is by no means simple, though. You’ll need to prove that you’re worthy of respect, and the way to do that varies with each character. Choosing whether to suck up to someone, stand your ground, or simply leave them alone can have a profound impact on your relationship with your squad as well as the outcome of quests. It’s possible to lose access to entire plotlines and characters because of a careless word. Fortunately, Dragonfall’s conversation system is as good as any I’ve seen in a game. In some cases, you need to carefully read your conversation partner, sizing up their tone, their needs, their relative power, and how you can turn any of those things to your advantage. This might mean anything from flattering a potential employer for a job to threatening a janitor out of sounding an alarm. In other cases, your skills come into play. Dragonfall has a complex skill progression system and is fairly stingy about doling out XP, or “karma.” You can invest these karma points in attributes (such as strength or charisma) or skills (such as close combat or summoning), but your level in any skill can never be higher than the attribute that governs it (so with five points strength, you could have a maximum of five in close combat, for instance). In addition, the cost to buy these increases by one each level. What all this means is that you need to invest your karma carefully. You’ll probably never max out more than one or two skills, and spreading yourself too thin will leave you woefully underpowered. It’s much better to go down a path you find interesting and roleplay around it. The integration of these skills with conversation and exploration is one of the things that makes Dragonfall a masterpiece. Your karma investments will pay off in unexpected ways as you play. Maybe your knowledge of medicine will help you identify a dangerous substance or your aptitude as a spell caster will help you astrally track a target. Some skills will come into play far more often than others — decking, or hacking, will constantly get you out of jams — but the strict upgrade economy keeps you from gaming the system, which makes these successful skill checks feel all the more organic and satisfying. The right combination of skills and good dialogue choices can even get you through some missions without firing a single bullet. Dragonfall shines just a bit less in combat. Victory relies heavily on strategic positioning, use of cover, and rationing your limited action points. While not quite as unforgiving as something like XCOM, the game has pretty low tolerance for mistakes, making planning and frequent use of support abilities a must. What’s more, you can often manipulate the environment to your advantage, particularly if you’re a decker or shaman. Admittedly, all of that sounds pretty thrilling, but it gets old by the game’s end. Despite the fact that you regularly receive new abilities to use in battle, the core gameplay remains the same. Using a different ability or weapon mostly just means doing more damage or hitting at a longer range, and like in XCOM your squadmates have the frustrating tendency to whiff repeatedly even when their attacks have a 90%+ chance of hitting. There’s nothing wrong with the combat, and it was good enough to hold my attention through the end; I just wish it had the dynamism and inventiveness that enliven every other part of the game. It’s worth mentioning the Matrix, since it’s a major differentiator for the game, even though in practice it’s just a jankier version of combat. Well before Keanu Reeves stuck it to the Man and expressionlessly saved humanity from evil squid robots, the term “the Matrix” was used to describe a digital landscape. In Dragonfall you explore this space primarily to steal valuable corporate secrets, but sometimes to access locked doors or other bypass other security measures. This plays out on an alternate map with basically the same rules that govern combat in the real world as you fight representations of security programs protecting their data. The difference is that only one character can enter at a time, and only if they have a cyberdeck. Your available abilities are also much more limited, and since your chance to hit is calculated differently, you tend to be less accurate as well. It’s probably the biggest missed opportunity of the franchise, though experiencing it is almost entirely optional. While some of Dragonfall’s mechanics may wear thin, its world never does. The Flux State is a fascinating setting, packed with interesting characters, political intrigue, and a keen sense of having been lived in and worn out. Evocative text passages precede level transitions that set the stage for what’s to come and fill out the world in a way that cutscenes would struggle to do. While the graphics are nothing mind-blowing, they’re certainly stylish, and the game’s solid art direction makes the world come alive, especially in the Kreuzbasar. The game’s sound carries far more than its own weight, lending life to mostly still backdrops with the clever use of crowd noise, rumbling subway trains, and the dull hum of sterile offices to sell environments. And though you’ll hear a lot of the same songs repeated throughout the game, they’re tonally perfect and never got old for me. I constantly felt myself wanting to pull up a seat in the Kreuzbasar’s coffee shop or stop to peruse a street vendor’s drones. Dragonfall depicts a world completely under the heel of otherworldly monsters and capitalism run amok, but it’s still teeming with humor and humanity, from surprising encounters like meeting the self-made king of an abandoned laboratory to sharing a quiet moment of reflection with your team after a botched run. In Dragonfall, you’re always a job away from starving, a step ahead of those who want you dead, but its vision is so compelling, it gives this squalor its own kind of grandeur. |

Archives

May 2018

Categories |