Like a blend of RoboCop and Blade Runner without the satire or existential dread, Synthetik casts you as a literal killing machine sent to destroy a legion of intelligent androids. While its central mechanics will be familiar to anyone who’s played a rogue-lite shooter before, its innovative gunplay and deep upgrade system offer plenty of reasons to embark on run after run. As with most games in the genre, Synthetik sends you through a series of procedurally generated levels with nothing but obscene amounts of firepower at your side. Each of the game’s four classes starts with a handgun and a dash move, along with a suite of specialized abilities and items. Nothing revolutionary, but it’s the first sign that Synthetik has more going on than the typical top-down shooter. Loadouts for each class are well tuned for a different style of gameplay, encouraging anything from high-risk tactics to stealth and precision. Even fundamental mechanics such as healing work differently from class to class. Of course, this variety only matters if the game is fun, and fortunately, Synthetik makes committing violence on your fellow androids satisfying indeed. The game has lots of clever intricacies built in that engage your mind as much as your reflexes. For instance, standing still increases your accuracy, which turns gun fights into dances of positioning and evasion. Firing your weapon causes it to build up heat. Let it overheat, and you’ll take serious damage. To reload, you need to manually eject your clip -- losing any unspent bullets in the process -- then press another button to load the next round. Like in Gears of War, you can then press that button when a reload indicator on your screen hits its sweet spot to instantly finishing loading your weapon and gain a damage boost. On top of that, guns can jam, leaving you desperately tapping your keyboard to clear the chamber in the middle of a firefight. All this complexity can be overwhelming on your first few runs, but once you get the hang of it, you’ll be ready for even more complexity when you start plumbing the depths of the upgrade system. As you play, you’ll gain experience, credits, and data. Experience, predictably enough, levels up your character, granting new passive buffs and strengthening core abilities. Credits are used to buy and upgrade items within the level and are lost when you die. Data is probably the most interesting of these currencies; you keep what you’ve collected when you die and use it to purchase new starting weapons or permanent upgrades that apply across all classes. Yet another layer is the weapon upgrade system. Weapons can be found in chests throughout the level, and the sheer variety is staggering. You’ll find everything from pistols to lightning cannons, and each time you pick one up you have a change of getting a named variation that has different stats or drastically alters its behavior. Upgrade kits are also scattered around, each buffing your weapon and giving you a choice between three randomized attachments that add further perks. It’s incredible that this Jenga tower of systems can support its own weight, and nigh miraculous how well the pieces play off of each other. On paper it sounds like a chaotic mess, but when you’re in the thick of it, you hardly think about the dozen different factors that define your strengths and weaknesses. With so many random elements in the mix, it’s impossible to build a fully optimized character. You just pick which class you want to play and hope to find complementary weapons during your run. Even if you don’t quite find what you wanted, some combination of upgrades, abilities, items, and weapons is bound to synergize. With all these levels of augmentation, a long-range shotgun that fires ricocheting rounds and occasionally launches missiles is not out of the question. Get far enough into the game and even this absurd amount of firepower may not seem like enough. Players usually go into rogue-lites seeking a challenge, and Synthetik doesn’t fail to deliver. With a seemingly unlimited number of ways to kill you, the game never entirely lets players off the hook. It doesn’t matter how powerful your arsenal is when you take a barrage of missiles to the face. Every level is punishing, but bosses are downright brutal. They’ll push your skills to the limit as they shrug off your gunfire while filling the screen with flak. Fortunately, you have several ways of dealing with the challenge. Synthetik has a modular difficulty level that allows you to configure a dozen different aspects of the gameplay to suit your taste. If you still find yourself outgunned, you can always bring in reinforcements, thanks to the game’s simple online multiplayer mode. From the main menu, you can search for open lobbies or start your own, and as long as you’re online you can chat with other players regardless of whether you’re in the same lobby. It isn’t the most active online community, but I never had much trouble finding a teammate when I wanted one. Synthetik’s graphics and sound are well done, but they’re obviously secondary to gameplay. Aside from a theme song that might as well just be a remix of the Stranger Things theme, there’s not much music to speak of. Sound effects are also sparse, but they pack a visceral punch, especially when you’re using heavy weapons. The game’s graphics are more notable. Only a few of the enemy designs were particularly interesting, but they’re all painted in broad patches of vibrant color and stand out clearly even in the midst of a hectic firefight. Visually, everything has a sterile, mechanical menace that suits the game well, even when it isn’t otherwise that impressive. Synthetik is a masterful rogue-lite, but it still shares the genre’s biggest problem. There’s a slight irony to the way that games built around randomness and variation inevitably start to feel a little repetitive. Running through the same gameplay loop as you die over and over is bound to get boring after a while, and randomized weapons and enemies can only do so much to mitigate that. Synthetik doesn’t address that issue, trying instead to make its central loop as fun and technically fulfilling as possible. While it succeeds extraordinarily well there, it still makes no concessions to players’ limited time or patience as they repeatedly throw themselves toward almost certain death. Even though I had to eventually accept that I would never master Synthetik, it was still a joy to fail at, time and time again.

0 Comments

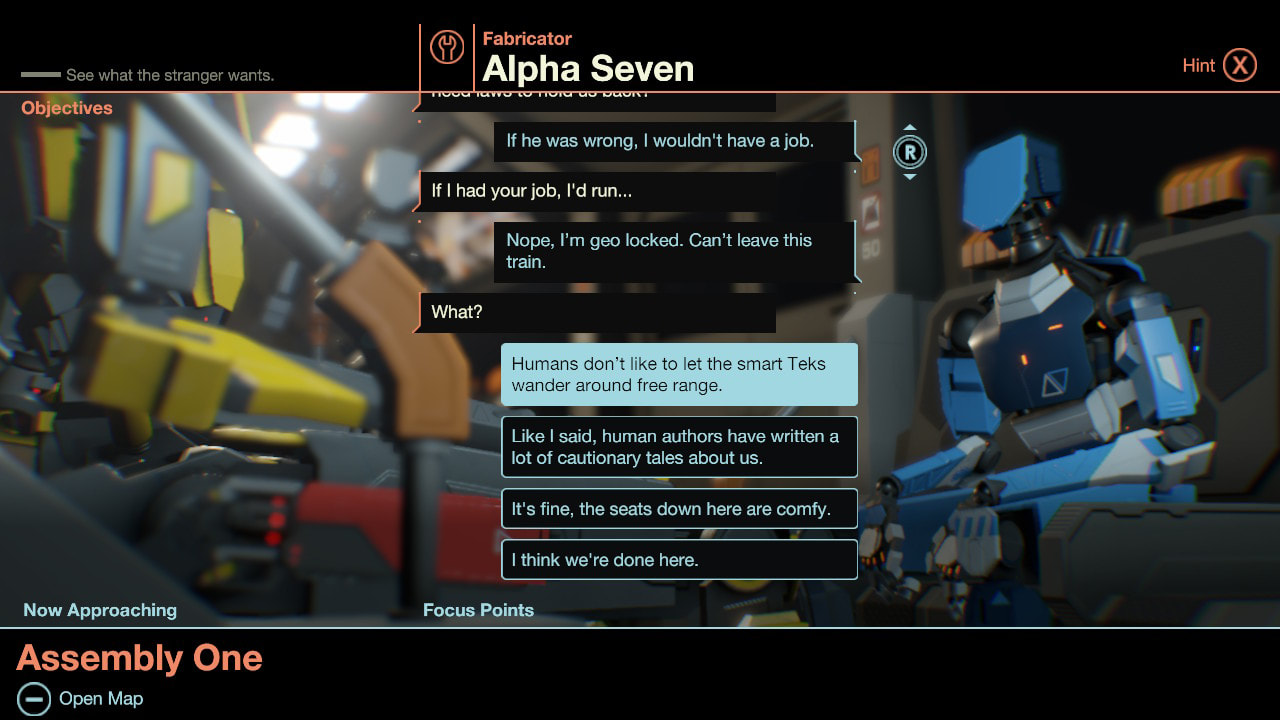

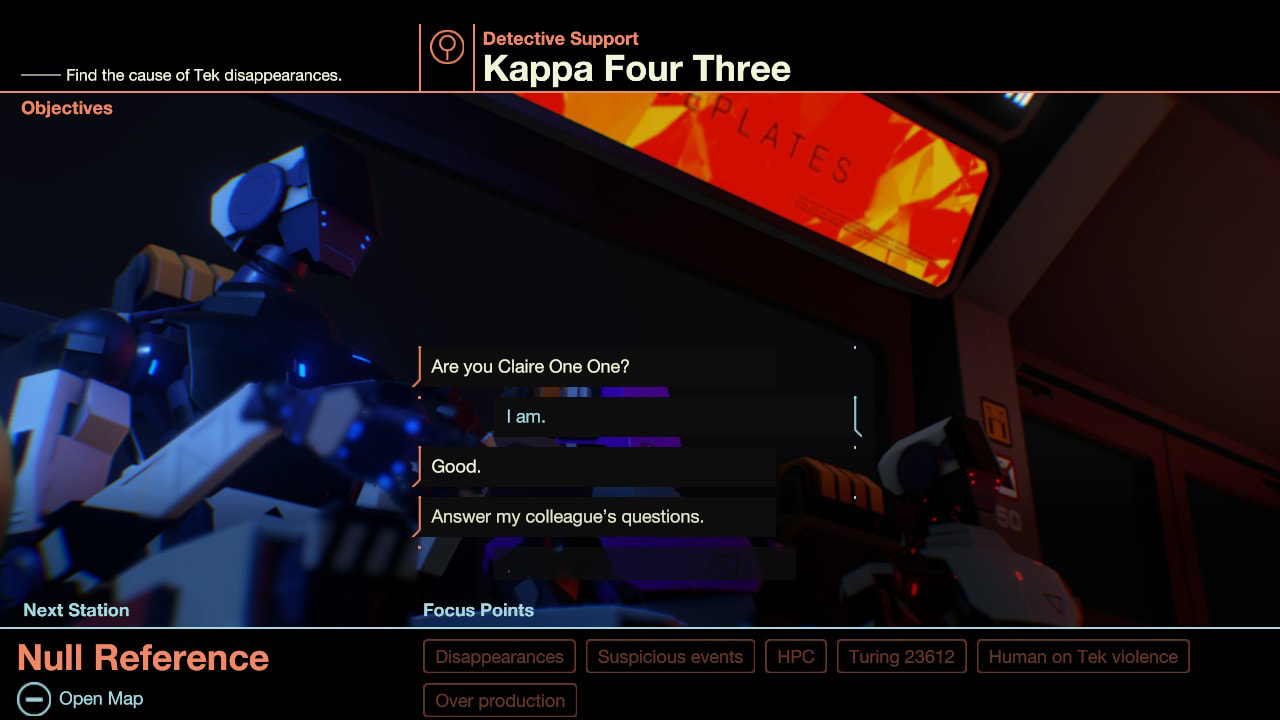

If no one sets out to make a bad game, then even the biggest failure must have a good idea at its core. At least that’s what I thought until I played Castle of Heart. What I had seen of the game before I played it led me to expect a middling action platformer, but something about it hinted that I might be pleasantly surprised once I dug in. And surprised I was, but in a way that made me wish the game even approached mediocrity. In Castle of Heart, you’ll ride moving platforms, jump across crumbling scaffolds, and swing across ropes through 20 uninspired levels. You play as a knight turned to stone by an evil sorcerer, but saved by the tears of your beloved, which is just as corny and tone deaf as it sounds. It would feel more problematic that your love interest is only defined in relation to your mighty male hero if every other character weren’t equally shallow. No one even gets a name. The only consequence of the story comes through two bewilderingly bad mechanics. You constantly lose health as a result of the curse, so you need to keep picking up health orbs scattered around the level or dropped by defeated enemies. Losing health over time like this discourages exploration, and it made me want to avoid combat as well, since in later levels the orbs dropped by enemies don’t make up for the health you’ll lose fighting them. Once your health gets critically low, one of your arms turns back to stone and falls off. This leaves you unable items or secondary weapons, which just feels like getting kicked when you’re down. These items, when they’re available, add a nominal amount of variety to the combat. You can find throwing knives and a number of grenades, a few of which can freeze enemies or set them ablaze, scattered throughout the levels. My main strategy for these was to save as many as possible until I hit one of the game’s wild difficulty spikes, then use them to burn through the tidal waves of enemies thrown at me. You’ll also find ranged weapons in the form of crossbows and spears, which are helpful for taking down flying enemies but are generally too slow to use at close range. You’re much better off just picking up a secondary melee weapon, since your default sword is about as effective as papier mache against later levels’ enemies. It doesn’t matter which weapon you use, since none of them change your moveset or even your attack speed. You always have the same default attack, plus a stronger strike that can break walls but depletes some of your health. That’s basically all there is to combat. You have a dodge roll, but you can’t roll through enemies. It’s more of a slow somersault, really, and it usually takes you longer to roll away from your opponent than for them to finish an attack. You’re able to block, but its animation is just as lethargic, and a successful block only buys you enough time to make one counterattack, if that. You can’t reliably stagger foes, so your melee options come down to repeatedly jumping over enemies’ heads to backstab them or just charging head on and hoping they go down quickly. Some games make this dumb bull-rush strategy enjoyable, but Castle of Heart’s weapons have no heft to them, so jamming the attack button to make your knight flail his weapon in the enemy’s direction feels just as empty as it sounds. In the final area, enemies gain the ability to teleport, removing any possibility for strategic positioning. Trying to play intelligently and avoid damage just drew the game out longer, and by the last few levels I resorted to avoiding fights entirely and making a beeline for the exit. This, too, has a cost in this plodding game. In addition to health pickups, enemies drop energy orbs. Collect enough of these and you’ll permanently extend your life bar, a fact that the game never bothers to explain. You can also find them scattered around the level, but you won’t collect enough without facing enemies. That means that choosing to spare myself the agony of playing this game any longer than I had to made me progressively more ill-equipped to face it. Checkpoints are at least sprinkled liberally throughout so you don’t have to replay too much of a level when you die, an act of true mercy by the developers. The level design itself gives you no sense of how the terrain is connected and makes no attempt at building a believable environment. Aside from the first area’s ugly medieval countryside, they at least provide a fairly pretty background to look at as you trudge through. Every level is functionally the same, though. You’ll hop over pits and platforms that dot the landscape randomly, with set pieces like sliding downhill or running from unstoppable hazards while dodging obstacles sprinkled in every few levels. In one of these, you’re being chased downhill by a few rolling logs that you could easily jump over if only the game didn’t kill you for trying it. Each level also has six hidden crystals, if for some reason you’re inspired to explore the secret areas that are often indistinguishable from bottomless pits. I collected all of them in one level and got no acknowledgement from the game. I can only assume that finding every one in the game unlocks something, but nothing short of a threat to my life would motivate me to go back and try. It’s not that the platforming itself is always a miserable experience, it just isn’t any fun. You don’t so much jump as you do float, but once you get used to the moonlike gravity, it’s mostly functional. Even on solid ground, your movements are so ponderous that it looks like you’re wading through molasses. The game’s four bosses don’t shake things up much. The first two are just melee attackers with a couple of unique moves and awkward, unclear animations. I had to pause the game when the first boss’s flailing animations sent me into a laughing fit, the first of many I had while playing. The last two bosses mix up the formula a little, with the showdown against final boss being the only fight in the game that approached enjoyable. Facing him is the only time when you’re up against even a minimally varied moveset, and more importantly, an intelligible attack pattern. It was during the third boss fight that I finally hit on what was bothering me most about he combat. It feels almost as if your character’s combat mechanics and the enemies’ were designed without one another in mind. Projectiles move too quickly to dodge, blocking attacks gives you no advantage, and later levels have so many enemies attacking you at once that there’s no viable way to take them on. It’s not that enemies are particularly tough or cunning on their own, the game just doesn’t give you any way to counter them. This may sound suspiciously like Stockholm Syndrome, but at certain points I actually found myself enjoying Castle of Heart, not in spite of all the things it did wrong, but because of them. At times, it is sublimely bad. When I would continually get thrown off a rope at an odd angle into a chasm or get surrounded by teleporting enemies in a doorway and die within one second, I found myself laughing as I shouted at the game. Sure, other times it made me absolutely livid, and I was miserable by the end, but at some points it was fun in the way that movies like The Room are fun. The game doesn’t feel mean or unforgiving, it’s just so bumbling and awkward, so full of inexplicable design choices, that it has a sort of shambling charm. It’s a faceplant of a game with almost no redeeming qualities, but the sheer number of ways it fails is impressive in a way. After Castle of Heart’s first level, I was looking forward to breezing through a comfortably average game and quickly forgetting about it. By about the third level, that expectation had been shattered. That process repeated again and again; every time I thought I had a handle on how bad the game was, it got worse. When I beat it, I felt no sense of accomplishment but I was flooded with relief. On the other hand, I don’t think I’ll forget this one for a very long time.  A two-hour subway journey may sound like a commuter’s worst nightmare, but Subsurface Circular manages to make it both engaging and enlightening. Though to be fair, the game casts you as a robot who doesn’t seem to be capable of boredom. Developed by Bithell Games, creator of Thomas Was Alone and Volume, Subsurface Circular is intended to kick off a new series of short, experimental narrative games. Appropriately known as “Bithell Shorts,” they’re meant to be both developed and played quickly. The series’ first outing is a roughly two-hour text adventure dressed up with fancy art and music and was developed in just four months. In it, you play as a detective riding the rails between assignments. Over the course of the game, you don’t once move from your seat, which the game tells you is because humans aren’t comfortable with a machine of your intelligence wandering freely. Bolting a detective to their seat seems like a strange way to get crimes solved, but I’m no roboticist. In the game’s opening sequence, you’re approached by another robot, or “Tek” in the game’s parlance, who enlists you to investigate his friend’s disappearance. From the outset, Subsurface Circular makes it clear that you aren’t calling the shots. You’re immobile, for one, and you have no choice in whether to take this stranger’s case. Throughout the game, you’re constantly held hostage to others’ emotional whims. To get answers from your fellow passengers, you’ll generally need to do them favors or find other ways around their stubbornness. The game is divided into discrete chapters in which you must gather information to advance your case. In each section, a number of Teks will board your train car and you’ll question them using a simple conversation menu that designer Mike Bithell said constitutes the game’s “levels.” The UI is sparse and clean, letting you focus on what’s being said rather than fussing with menu selections. It also affords you a clear view of the train car and your conversation partner. While Teks are all faceless, their designs and movements do a remarkable job of imparting them with personality. Most of that personality, however, comes from the game’s fantastic writing. Even the best games sometimes slip into stereotypes, but Subsurface Circular skillfully molds its characters into individuals. Likewise, your dialogue options do an excellent job of letting you flesh out your protagonist without resorting to the hero/asshole binary that plagues so many other games. The game doesn’t make progress contingent on your behaving a certain way; your options are there for you to shape your character. I found myself considering my words deliberately, not because I had something to gain, but because I cared about what kind of person my character was. When someone says something that might be pertinent in the course of your conversation, you’ll unlock a new “focus point,” which you can then explore with them or other Teks. These focus points basically serve as keys used to solve the game’s conversational puzzles. Sometimes you have to solve literal logic puzzles, but most often you’re dealing with the much subtler challenge of piecing together information gained from a dozen different dialogues to get what you want from another character. There isn’t a lot of deep interaction involved, but some of these encounters can go in unexpected directions much in the way real conversations do, which may be even more satisfying. My favorite conversation in the game involves manipulating a Tek’s emotional state to get multiple responses to the same focus points. It’s an inventive way to solve a puzzle and it rings true emotionally. I wish that more of the game’s stages did as good a job of combining mechanics and story. Most of the time, while you are free to choose your responses, they have no almost bearing on the game’s outcome. You could get through a lot of the game by going through focus points in order and responding randomly to NPCs’ reactions; choosing different dialogue options just colors the way other Teks speak to you. How you feel about will have a huge effect on how you feel about the game. Some players will undoubtedly feel slighted by its linearity, but if you interpret it as a tale about the boundaries of free will, your lack of agency is in some ways necessary. Subsurface Circular isn’t concerned with branching paths or epic plotlines, instead focusing in on character development, expert worldbuilding, and extreme narrative efficiency. From your humble seat on the train, you’ll glimpse an automated world steeped in fascinating characters and hidden turmoil. The game touches on job automation, worker alienation, the inequities of capitalism, and the human tendency to distrust the unfamiliar, without ever feeling like a lecture. At times it borrows from the rhetoric of real-world issues, most notably immigrant rights, but it deftly avoids turning into an allegory. Where lesser storytellers would use the Teks’ struggles as stand-ins for modern-day woes, Bithell is careful to avoid equating them in a way that might seem crass or dehumanizing. The story is a mystery at its core, so I can’t give much more than the broad strokes without diminishing your experience of it. It takes some genuinely surprising turns without ever relying on cheap twists or shock value, and even its more prosaic elements held my interest. The last third or so of the game contains some brilliant mechanical and narrative inversions that left me absolutely floored and made me question whose interests I was serving and why. While Subsurface Circular tackles weighty subjects, it usually drops its plot points with a minimum of fanfare. Camera angles generally stay fixed throughout your conversations, and animations are ambient, reflecting the train car’s jostling and Teks’ fidgeting rather than conveying action. Its sound is similarly subdued. Chapters are punctuated by a great synthy score -- the opening song in particular is a banger -- but the game’s sonic landscape mainly comprises the rhythmic hum of the subway and the clicks of your interface selections. In the Switch port, your controller rumbles in time with the train’s movement, adding an extra link between you and the game world. Playing in handheld mode also allows you to peek down the train car by turning your Switch left and right, and to select dialogue on the touch screen. There’s some strange synchronicity between the Switch and Subsurface Circular’s interface that enhanced the experience, however subtly. As another bonus, you unlock a developer commentary after finishing the game. This mode cleverly inserts a Tek representing the game’s designer into your train car, who you can talk to using the game’s existing dialogue interface. It won’t change your perspective of the game too much, but it contains plenty of interesting insights and offers a good excuse to immerse yourself in the game’s atmosphere again. While the isn’t perfect, it’s closer than you might expect and it packs an incredible amount of depth into an unassuming package. If you’re even remotely interested in narrative games, you owe it to yourself to play Subsurface Circular. It’s an engrossing experience in its own right, and it feels like a herald of things to come for the genre.  From the street outside one of Berlin’s infamous all-night dance clubs, you can already hear the thumping bass and the excited shrieks of the crowd. It’s the middle of the night; the street is empty except for a bouncer standing between you and a night of debauchery. He looks cute so you try to flirt your way in. It seems to be working until one wrong word gets him angry. Your best bet now is to try to intimidate him into stepping aside. This guy is tougher than he looks. He takes offense and there’s no way he’s letting you in now. In moments like this, we’ve all wished we could turn back time just enough to preempt a mistake or two. In All Walls Must Fall, that option is always on the table. Developed by Berlin-based inbetweengames, All Walls Must Fall is a neo-noir cyberpunk alternate-history Cold-War time-travel techno thriller. Wait, let me try that again. All Walls Must Fall is a turn-based strategy game with procedurally generated levels set in 2089, in an imagined universe where the Soviet Union never fell. Or maybe it did fall and then someone went back to make sure it didn’t. You play as Kai, an operative sent into Berlin’s underground club scene by the state’s time-traveling investigation bureau, STASIS, to prevent a nuclear bomb from going off. Or rather, a bomb has already gone off, and you’re sent back in time to make sure it will never have been there in the first place. Look, time travel complicates a lot of things, from police work to grammar. Your biggest advantage in All Walls Must Fall is being able to make sure that things are complicated in your favor. In practical terms, that means manipulating the timeline as you move through cramped night clubs packed with identical partiers, avoiding or annihilating enemies on the way to your mission’s objective. You do so aided by the ability to undo your last action, or to send either Kai or his enemies a few seconds back in time. This can be used to reverse damage you’ve taken, for instance, or to rush through a room full of guards then reset them to a time before they knew you were there. The clubs you explore are full of weapon scanners, security cameras, and locked doors, which you can hack to remain in the shadows or just barrel through to attract the attention of guards. Hacking uses up your Time Resource, a bluntly named commodity that’s also consumed when you use your time-twisting powers. By default, Time Resource also constantly depletes as you play, adding a sense of urgency, though this option can be turned off if you’d prefer more of a saunter through Berlin’s seedy underbelly. Time Resource is gained by winning fights and by exploring the level. As is sometimes the case with procedurally generated levels, the clubs in All Walls Must Fall have no individual character. Taken out of context, the rooms often do a good job of portraying the grungy but euphoric atmosphere of an after-hours club, or at least what one might look like in 2089. But each club repeats the same few rooms in a different order, often packing in plenty of dead ends and improbable numbers of storage closets. As a result, you never feel like you’re moving through a real place. Adding to the persistent dissociation, NPCs share just a few basic designs. This is partially explained in-game by bringing up the idea that many of them are clones, but that doesn’t make it any more interesting to look at. At least the music suits the game, though it too is repetitive. Most of the game is underscored by a simple pulsing beat, which helps sell the club environments more than any other element. At the end of each successful combat, you watch a replay of the action timed to music. It’s stylish and fun to watch, but it’s the only time this syncing of music and visuals occurs. You can sneak your way through entire missions without firing a shot, and even if you’re spotted, potential enemies are generally willing to hear you out as long as you haven’t done anything aggressive. The point of All Walls Must Fall’s conversation minigame is to get your way by either threatening people, flirting with them, or just convincing them that you’re important enough to listen to. Kai is equipped with implants that allow him to see a person’s exact emotional state, so you’ll know which emotions your statements are triggering. The idea of using your time manipulation powers to erase faux pas and get information from your enemies is interesting in theory, but lacking in practice. Kai is given four random options for each of his responses, chosen from a tiny pool of potential lines. The same goes for his adversaries, so it often feels like you’re having the same conversation over and over. Your dialogue options are so clearly calibrated toward one emotional response or another that you can reliably use the same lines on just about every enemy and get a predictable result. The only wrinkle comes when you’re speaking to critical NPCs to complete mission objectives. They have their own dialogue options and personalities, and they show off just how satisfying this system could be if your enemies were more than cardboard cutouts. If you’re not in the mood to chat, violence is always an option, which plays out in typical fashion for turn-based strategy. You’ll alternate between trading shots with your foes and heading for cover, using your time manipulation powers to negate damage and instantly reposition yourself on the battlefield. Since you only have Kai to control and enemies all take their turns at the same time, fights move at a rapid pace. I found the combat exciting at first, but it quickly became as stale as the game’s conversations and environments. With only a handful of powers and weapons at your disposal, your strategic options are limited, and the game’s procedurally generated rooms don’t always lend themselves to clever positioning. Most of the time you can get away with staying behind cover and firing your default pistol wildly at enemies, rewinding time to heal your wounds whenever you get hit. Low-level enemies are identical, and though foes with time-shifting abilities of their own appear after the first few missions, their powers just let them teleport closer to you and grant them immunity to being stunned. All Walls Must Fall is built on a lot of interesting ideas, but that doesn’t make it an interesting game. Though it has plenty of style, it’s severely lacking in substance to back it up. Between the looping music, the indistinguishable levels, and the repetitive combat, I spent most of the game feeling like I was experiencing deja vu. It’s almost as if every element of the game were a metacommentary of its theme of recursive time travel, albeit an extremely boring one. In an industry where the biggest hits tend ever more toward complex mechanics, convoluted plots, and just cramming in as much content as possible, puzzle games remain one niche where developers can take simple ideas and iterate on them to perfection. That's the case with DYO, a co-op puzzle game about two minotaur best buds trying to escape a labyrinth through the power of friendship and split screens.

Growing out of a student project, DYO was created by just four people, a fact that shows in both its tiny scope and its extreme focus. Levels are constructed from a pretty limited set of basic parts, often just a few repeating floor tiles. The graphics are equally understated, but have a painterly charm to them. Your minotaurs are cartoonish and cute, and their animations effective but minimal. Sound design is subtle as well, with lots of quiet echoing that does a good job of selling the enormity and emptiness of the labyrinth the minotaurs are trapped in. This low-key presentation keeps the focus tight on the game’s clever mechanics and puzzle design. DYO can be played solo, but it’s built from the ground up for co-op. Its flexible control scheme allows for any setup from two controllers to one keyboard to control both characters. Each of the game's 30 levels sees the players guiding their respective minotaurs to separate exits. The thing is, the architecture of the levels makes these exits impossible to reach by simple traversal. In order to escape, players must use a handful of tricks based around manipulating the game's split screen. Each minotaur lives in one half of the screen, with the camera following closely as they move around the level. At any time, either player can "lock" their half of the screen in place, effectively erasing anything that's not currently in view. If both players lock their screens into position with nothing separating them, their minotaurs can the move freely about the entire screen. You can use this trick to remove walls, turn a series of solid floors into staggered platforms, and pull off plenty of other shenanigans by the game's end. The only other real "powers" you ever receive are the ability to swap the horizontal positions of the two split screens (a situationally useful maneuver that I became obsessed with using in every level once it was introduced) and a rewind ability that's used to reverse mistakes you've made. Later levels feature special qualities built into the environment that further complicate things. One series of levels centers around pushing blocks, another has walls and platforms that exist on your screen only when your partner can see them on theirs, and a third plays with scale by making everything on one side of the screen dramatically larger than the other. This last set of levels led to some moments of wailing laughter between my fellow player and I when a tiny minotaur got up to some Honey I Shrunk the Kids-style hijinks, like being forced to carry its gargantuan comrade around. These simple building blocks combine in continually surprising ways as the game progresses. Hard-won solutions to earlier puzzles quickly become part of the game’s lexicon, to be pulled up without a thought in later levels. DYO’s logic is like nothing I’ve ever seen before, but it became second nature so quickly that I swear I could feel it rewiring bits of my brain as I played. Despite the beautiful simplicity of the mechanics and the excellent way levels are constructed around them, it's the interaction with your co-op pal that really makes DYO shine. Again, the game can be played alone, and it still functions as an interesting puzzler, but it shines when you're playing on the couch with a friend. Being able to work things out together, each player experimenting on their own and in concert with each other to find the way to the exit, is a magical experience. My DYO partner and I would often get stuck, only for one of us see the path toward a solution and walk the uncomprehending other player through the steps until we were back in sync again. Nearly every one of the later levels saw us almost giving up before we came upon the answer together, the logic of the level suddenly making perfect sense. It was all the more satisfying because the game offers so little in the way of clues, trusting you to work things out as a team. And without fail, every time we found our way through a tricky level, we would erupt in cheers as our two minotaur friends celebrated with a triumphant high-five. If I have one complaint about the puzzles, it's that a little too often we stumbled on the answer through stubborn trial-and-error, sometimes not knowing exactly what we were even trying to do. On the other hand, that also left the door open for the numerous thrilling times when we finished a level absolutely certain that we'd done so in a way the developers didn't intend. DYO constantly surprised me. Belying its humble presentation, it unfolds into a truly unique puzzle game and one of the best co-op experiences I've had in a long time. It's short but satisfying, and a level editor currently being beta-tested may end up adding hours of content to the game. But even if you only ever play the four or so hours of content currently available, it's an easy recommendation. The only things you need are a good partner and some patience. If you have those, DYO's inspired mechanics and dazzling simplicity make it an essential experience. Once the cornerstones of the arcade, sci-fi shoot-em-ups have fallen from a place of pride to a rather small niche. By paying homage to its predecessors and adding new gameplay twists, Defenders of Ekron tries its hardest to restore the beleaguered shmup genre to its former glory. While it doesn’t quite succeed, its blend of retro aesthetics and innovative mechanics will surely win it some diehard fans.

On a basic level, Defenders of Ekron’s gameplay is pretty standard for the genre. Enemies shoot you, you shoot them back, all over the backdrop of a planetary civil war. After a few introductory stages, Defenders of Ekron settles into a Mega Man-esque loop of plowing through levels to defeat their bosses and gain new powers. You start with a basic blaster, a punchier cannon, and a shield, but before long you’ll gain blades for melee attacks, a dash move, and a few other fun weapons. At first glance, Defenders of Ekron doesn’t stand out much. Its enemy and ship sprites come across better in motion than they do in screenshots, but they’re still not particularly good looking. Some of the ship designs are interesting, especially for the many screen-filling bosses that you’ll encounter during the game, and a few of the backgrounds are arresting, though a bit too repetitive. The game’s standout art appears at home base, which features several semi-animated backgrounds with the hand-crafted look of matte paintings from a 1980s sci-fi movie. Friendly NPCs all get large portraits done in a similar style, most of which look interesting and are made with care. That style also turns out to be a perfect complement to the game’s story, which has all the hallmarks of an ‘80s kids’ anime. Giant mechs piloted by teenagers, gleefully overwrought villains, shoddy dialogue translation, second-act double-crosses, inexplicable emotional blowouts between the protagonist and his friends — it’s all there, and it’s all corny as hell in the best way. The game packs way more lore than it needs to into codex entries throughout the world, which helps to establish a fairly intricate stage upon which the game’s story unfolds. Instead of the ever-upward level path of most shmups, the game’s levels feature sprawling exteriors that you can navigate at will, intercut with cramped dungeons full of puzzles and baddies. It’s a welcome twist on the spartan level design that dominates the genre, which often leaves players with little sense of where they are in space or how far they’ve traveled. Unfortunately, Defenders of Ekron’s levels are more novel than they are interesting. The free-roam maps tend to be expansive and repetitive, while the dungeons are usually series of rooms unartfully cobbled together like leftover LEGOs. Progressing through them can be tedious, especially when sparse checkpoints force you to recross the same wasteland, fight the same enemies, or solve the same puzzles over again when you die. And believe me, you will die. A lot. Defenders of Ekron rides the line between satisfying difficulty and controlling-throwing aggravation. There’s a lot of fair challenge built into its bullet hell formula, but several mechanics ramp up the frustration rather than the fun. Your ship’s hit box seems just a bit too large, and your shield takes a touch longer than it should to activate. The game’s wonky recharge mechanics complicate things as well. Using any of your abilities, including your basic attack, eats energy. To recharge it, you’ll need to momentarily stop using any abilities. The lag between laying off the trigger and gaining energy is fairly long; it seems odd that this isn’t activated by a button instead. Regenerating health has its own quirks as well. You gain “Oxus” by killing enemies, which can be traded in for upgrades back at base. This same resource is used to regenerate your health and to power a damage-boosting “Berserk” mode, forcing you to choose between immediate needs and long-term benefits. The constant risk-reward choices you’re forced to make add some depth to the gameplay, but the system has some flaws. These abilities are most useful in the midst of a hectic dogfight, but getting hit instantly cancels them, causing you to lose your hard-earned Oxus. It feels unnecessarily punishing, especially when you’re facing off against bosses that essentially fill the entire screen with bullets. Some of these bosses have fairly interesting patterns to master, but often they boil down to battles of attrition that relegate you to taking occasional potshots while dodging absurd amounts of projectiles. And if you make the bad decision that I did to focus on upgrading speed rather than firepower, you can look forward to spending practically an entire afternoon slowly chipping away at a boss’s health bar. If you find yourself short on Oxus for upgrades or you just like the game’s punishing difficulty, Defenders of Ekron also has an extensive collection of training challenges to complete, which reward you based on performance. The game’s upcoming Asian release also boasts a boss rush mode and an easy mode (which I would have had no shame activating right away), among other improvements. There’s no word on whether those enhancements will be making their way to North America. Even if they did, they wouldn’t be enough of an incentive for me to dive back back in. Though I really enjoyed the game’s cornball presentation, its gameplay too often felt like punching through a brick wall only to get to another brick wall. However, if you’re not bothered by constant repetition or the sense that the game wants to beat you up for your lunch money, Defenders of Ekron may be worth a look. Update: Since I wrote this review, Cellar Door Games has added an online matchmaking lobby to Full Metal Furies, alleviating one of my biggest issues with the game.

After the success of 2013's Rogue Legacy, developer Cellar Door Games had a lot to live up to. Rather than just expanding on the excellent foundations of its previous hit, the team decided to switch into hard mode by trying something entirely different. Full Metal Furies takes the classic arcade beat-em-up formula and adds layer upon layer to it to make something that feels both nostalgic and entirely new. Love it or hate it, the pixel art aesthetic suits Full Metal Furies perfectly. Each character and enemy is loaded with detail, with bosses appropriately being the most arresting. Fights often get visually chaotic, but they’re rarely confusing thanks to clear markers of who is targeting whom and what areas you should move away from if you don’t want to play catch with mortar fire. Sound cues are somewhat less clear, and the soundtrack sets the stage well whether it’s a hectic battle theme or chill camp tune but isn’t particularly interesting. Among the things that set the game apart are a base that expands as you play to hold all of your upgrades and acquisitions, and a surprisingly deep set of puzzles that have you gathering clues in both the overworld and the game's levels. These elements add depth and character, but you're really here for the combat. Built for co-op play, the game pits four unique characters, each upgradeable in myriad ways, against hordes of challenging enemies. Triss the tank excels at blocking and crowd control. Erin the engineer can lock down enemies and dodge away before they retaliate. Alex the fighter leaps around the battlefield dealing massive damage. Meg the sniper keeps enemies at bay with mines and rifles. No matter your preferred playstyle, you'll likely click with at least one of the Furies. Over the course of the game, I switched characters frequently and by the end it would have been impossible to pick a favorite. Their moves are simple on their own but chain together in tactically and viscerally satisfying ways. Each of the game's characters brings four skills into the fray. These roughly break down into a simple attack, a dodge, a power attack, and a more defensive move, but they're wildly different from each other in practice. For example, the "dodge" skill can be anything from a simple roll to a powerful dive bomb that knocks enemies away. The deeper you get into the game, the more complex it gets. Full Metal Furies has perhaps one of the best upgrade systems ever for a game of its type, allowing players to build and upgrade equipment as well as invest points in a stat/skill tree. A few of these stat upgrades just boost health or damage, which I'm never a fan of, as it encourages boring builds and functions as little more than a way to siphon cash away from more interesting upgrades. However, these trees also offer options to buff characters in more meaningful ways, such as adding new skills or modifying attacks. Much more interesting is the equipment system. Throughout the game, you can find blueprints which can be built and equipped at your base. Each piece of equipment purchased this way directly affects one your character's four skills. Some of these completely replace that skill with another, and even the more linear upgrades come with drawbacks that will alter the way you use the ability. Swapping loadouts this way keeps the game fresh and allows for seemingly limitless attack combinations when you factor in a whole party. Co-op combat is the core of Full Metal Furies, and it almost never disappoints. While each character is viable on her own, the Furies really shine when they work together. A full roster can have Triss knocking enemies to the floor with her charge where they can be swept up in Alex's whirlwind, all while Erin traps her foes with a flying drone and pistol and Meg picks off stragglers from a distance. Played with a full party, or even just a partner, Full Metal Furies is a frenetic, bullet-dodging riot that easily ranks among the best beat-em-ups ever. It's fortunate that a full team is the efficient killing machine that it is, because enemies can be downright brutal. If minotaurs with machine guns and charging attacks seem tough, just wait until they're combined with flying bomb drones, invisible snipers, and artillery strikes. Fortunately, checkpoints are generous and you gain experience even from failed runs, so the action keeps moving at a constantly escalating pace. At times the game turns into a straight-up fantasy bullet hell, putting your evasive skills to the test. In these moments, when you're weaving through a hail of gunfire, parrying melee strikes and diving over a missile strike zone while your partner ziplines across the battlefield to perfectly place a landmine before knocking a horde of enemies away with an explosive rifle shell, Full Metal Furies absolutely shines. There's so much variety to the action, from skills to enemy types, that this game could become a staple in any gaming group's rotation. However, this perfectly tuned co-op experience does have a downside. While the single-player mode is interesting in its own right, it pales in comparison to multiplayer. Solo players do have access to an interesting mechanic whereby they can switch between two team members (chosen between missions) on the fly. This allows you to set up some wild combos using the abilities of both characters. It has appeal as a sort of juggling act and should satisfying the kind of players who like a fast-paced skill testing type of gameplay, but it's disappointing from any other perspective. The game is just not meant to be played this way, and no other real concessions are made to solo players. What is an engaging challenge to rise to with friends becomes a reflex- and patience-testing chore alone. It's still fun for a while, but it eventually becomes a slog. What would be a small caveat becomes a deal-breaker due to the baffling decision by the developer not to include matchmaking in its co-op game. In response to a post of the game's Steam forum asking about online play, developer Cellar Door Games said, "We decided to make it invite only because it is a very heavy story-oriented game, so it didn't make much sense for people to suddenly drop-in to your campaign." This, frankly, is nonsense. There is no reason why a story-driven game couldn't have drop-in gameplay; it's a pretty standard feature in plenty of games of this exact type. And to call Full Metal Furies a "story-oriented game" is beyond a stretch. The story is that the Furies have to kill a couple Titans and shoot cute quips at each other between levels. It's a serviceable story, and it's exactly as much as the game needs, which is to say almost none. It's certainly not worth excluding a vital part of the game for, and without matchmaking, the game feels not only lacking but unfinished. The developers have tossed the community a bone by setting up an official Discord server where players can set up their own groups. It's a half-hearted concession, and a month after release the desolate server results in more unanswered requests than it does actual games. Review scores are imprecise at the best of times, and in this case even more so, so take it with the following grain of salt: If you plan on playing Full Metal Furies alone or finding teammates online, it's a fun but limited niche game that's good for a few hours of fun. But if you have a dedicated group of friends who can play together regularly, I wholeheartedly recommend it as one of the best games of its kind. The Station is a game about walking around and picking things up. In space!

Essentially a linear tour of a space station called the Espial with a story cobbled together from audio logs and environmental objects, The Station is pretty much the definition of "not for everyone." At the outset, it's somewhat difficult to tell exactly what to expect from it. Its first few minutes seem to suggest some kind of sci-fi horror puzzle game, but its controls aren't built for action. You can't jump, for one, and the buttons that would normally be devoted to turning aliens into goo are instead used to pick up coffee mugs and turn them around. This simple ability to spin objects that you're holding goes a surprisingly long way to help the environment feel solid and sell that idea that you're interacting with things manually. Its graphics also call to mind the 3D adventure games of the '90s, with gorgeously rendered environments crammed full of fairly static but odd and appealing set dressing. While The Station quickly settles into a linear storytelling game with light puzzles, that initial sense of not knowing what to expect persists, keeping the player constantly on edge about what may be lurking around the next corner. It's usually another coffee mug. The titular station is decidedly mundane compared to the settings of other sci-fi games. You'll find your share of warp drives and repair bots on the Espial, but they're far outnumbered by simple items from playing cards to pens to the aforementioned and ever-present coffee mugs. These simple elements help to ground the station in reality, making it feel like a place that’s inhabited by real people rather than a level that exists solely for the player. More importantly, the station's three crew members have their own bedrooms chock full of personal effects and character-building secrets. These are very much bedrooms rather than crew quarters; each one has a stunning amount of personal detail packed in to help flesh out its owner. Further character development comes from the copious audio logs and written notes you can find from each character. The voice actors are bombastic but believable and you get a good sense of who they are from even inconsequential recordings. It makes sense that a lot of effort was put into these recordings, because the game is so reliant on them that poor performances would basically torpedo the whole project. Yes, audio logs have become nigh unto a scourge in the last decade of game design, but at least these ones have an in-game reason for existing. In the lore of The Station, each character is outfitted with a futuristic Apple Watch that records audio automatically whenever its wearer is afraid, exhausted, or otherwise stressed, and it probably still can't hold a decent charge. The player character uses an augmented reality interface to listen to these logs, which are all mercifully short and generally do a good job of advancing the game's story with a minimum of immersion-breaking exposition. This same AR device is used to view the game's map and see objectives in the environment, which goes a long way toward making the world seem cohesive and real. For example, when you come across a locked door, you'll often see what key or action is required to open it, giving you new objectives organically and in fiction. Progressing through the game is rarely complicated, but the simplicity of the puzzles works in the game's favor in some ways. Rather than figuring out arcane sequences of triggers and rotating statues to open locked doors like in the 3D adventure games of old, you usually take fairly common sense steps to move through the ship. Finding spare parts for a maintenance robot means consulting an inventory manifest, for example, and the ship's crew members leave themselves hints to their locker combinations in their cabins, surely to the annoyance of their IT department. It all feeds back into what seems to be a mission statement for the developers to make the Espial as convincing and independent of the player as possible. What the puzzles lack in challenge, they make up for in veracity, making the "a-ha" moment of realizing a solution all the more rewarding. I thought this realistic approach to puzzle design was excellent, but I can see how it might be too simplistic for some. However, puzzles take a backseat to story in The Station. The big picture is that the Espial's crew is secretly observing a newly discovered planet that’s engaged in civil war when they suddenly go silent, and you are sent to investigate. The story unfolds at a good pace, with the player driving the discovery of each new piece of information. It's much less concerned with delivering a thrilling plot than raising intriguing questions and creating compelling characters, and it succeeds on both fronts. The game asks you to consider the way that humanity thinks about other species, and what they may think of us in turn, as well as calling into question notions of intelligence and isolationism. It does have some surprises in store for those willing to explore a little outside the critical path, and while its final twist is heavily foreshadowed if you’re looking closely, it still lands solidly. My only complaint about the story is that it seems satisfied to raise a lot of questions without really providing much of its own viewpoint. In regards to that twist, I do want to point out one particularly impressive bit of obfuscation the game pulls off. I'll keep it as vague as possible but if you've got a severe spoiler allergy you may want to skip this paragraph. Your main objective in the game is to find out what happened to the Espial's three crew members. At two points during the game, you'll come across space-suited corpses and see an on screen notification that you've figure out what happened to a crew member. Upon finding a third body, however, you don't immediately get that notification. You do get it just moments later, but doing so causes you to realize retroactively that finding those bodies was not necessarily how you found out what happened to the crew members. There were other indications in the environment that you were let in on but may not have realized their significance right away. It's a clever way of using the game's interface to mislead players that I just wanted to call out for how much it floored me when it hit. All in all, The Station is a short but satisfying game. It can easily be finished in a single session, and that may actually be the best way to complete it. It's worth stretching out the runtime slightly by taking your time to really examine the nooks and crannies of the Espial. Just make sure you go in without the expectation of really captivating gameplay or a sweeping narrative. If most big-budget sci-fi games are sweeping space operas of galaxy-spanning consequence, The Station is an understated short story with a small scope that just might make you think about your place in the world.  At its core, Symmetry is an extremely simple game. Like other survival sims of its type, you're tasked with monitoring the status of a small handful of people and using them to collect resources to keep themselves alive and ultimately escape their circumstances. Symmetry boils those systems down to the essentials. Your crew members have two stats: health and hunger, which they keep topped off by sleeping or eating. They have to gather three resources: wood, food, and scrap, which they use to heat the base, eat, and repair or upgrade stations, respectively. That essentially forms the whole basis of the game, with really only one complicating factor: cold. Your intrepid spacefolks find themselves stranded in Arctic conditions and nearly every decision needs to be weighed against the risk of freezing to death. To keep the base heated, someone has to gather wood from outside, where their health drops more rapidly. At first it's not a big problem, but the more wood the crew gathers, the farther they'll have to go to find more trees, putting themselves at ever-increasing risk of getting stuck too far out when a lethal cold snap hits. Wood burns quite quickly, meaning you'll either have to stockpile it or keep a near constant supply of lumber coming in. The crew can survive some time in a freezing base by making use of the regeneration chambers, but that keeps them from doing other work and it can get dicey when you have fewer chambers than you do people needing help and you have to play musical chairs for healing. I found this reliance on a steady stream of lumber to be mostly just an irritation. There are no breaks in the weather that allow you to ‘tough it out’ without the heater for a while, and no way to turn the furnace off to conserve fuel for when you need it most. The facility your crew inhabits is static as well, with no way to upgrade anything aside from the storage capacity for your various resources. I would have liked the option to improve my base a bit, maybe by adding additional health pods or food stations, increasing heaters' efficiency, or making machines less likely to break down. And boy would that last point go a long way. Making it out alive means stockpiling scrap to spend on a few expensive systems, but that scrap is constantly being depleted to repair systems. Like wood, it takes longer to gather the more of it you've already collected, but the escalation is considerably more drastic. You're constantly using the scrap that you wanted to use for upgrades just to keep the base running. It's a staple of survival games, but I just found the economy of it off in this case. I had scenarios late in the game where a series of cascading breakdowns reduced the hoard of scrap that I'd been saving the whole playthrough down to near zero in one swoop, with nothing I could have done to prevent it. The list of components that can fail is immense (power supply, weather station, healing pods, food generator, refrigerator, furnace, and a radiator in each room) and it's almost always a life-threatening emergency when one stops working. I kept wishing that the game gave the player more leeway to decide which components they found critical and formulate a strategy around them. If I were making a wishlist, a Faster Than Light-style system of strategically diverting power would be near the top. At the very top would probably be improvements not to machinery, but to the people who tend to it. Symmetry does distinguish its characters much more than the average survival sim, but the thin layer of personality it paints onto them almost makes their ultimate hollowness more noticeable. Throughout the game, crew members will spout dialogue to no one in particular that helps define them as characters and advance the nebulous plot. While some elements of the story are interesting, nothing ever gets fully fleshed out. Especially disappointing is a late game turn that seems to promise a severe change of plans for the crew, but fizzles before being resolved. I'm all for game narratives that aren't completely spelled out for players, but Symmetry tends to just let plot threads hang in the air. What really keeps the story from ever getting interesting is that the characters themselves never interact or build off of each other. There is hardly any indication that they're even aware of one another. The first time I had a crew member die, I was floored by the grim choice the game presented. Either bury the body, or use it to feed the remaining crew. I was wracked with guilt, but ultimately decided to go the utilitarian route. In a nice touch, the floor around the refrigerator became stained with blood for a while, but that was the only acknowledgement of what I'd done. The dead man's comrades just sprinkled a little Jacob on their cereal and went on with their day. Some sense of characters building relationships and working together would have made them much more interesting than the drones they seem to be for most of this game. The eerie blankness of the characters plays out mechanically as well. Crew members will continue doing whatever job you assign them until you change their orders, no matter what. They will mindlessly wander into -90 degree weather with their health almost depleted, then quickly freeze to death without a single word of complaint. There's also no way to simply cancel their orders and have them standby for further instruction. So when storms hit and you have characters who can only do gathering jobs outside the base, you're stuck following them around and ordering them to walk from one end of the structure to the other to keep them from walking themselves to certain death. This kind of tedious micromanagement gets more and more important as the game goes on, until in the end you're just babysitting a bunch of brain dead astronauts with a death wish. All other problems aside, the tedium is what really kills this game for me. That being said, I did play through the game a number of times. The gameplay is certainly addictive, though I wouldn't necessarily call that a good thing. But it does always seem like there's something interesting just around the corner, like if you do things right then next time you'll crack it. I can definitely see some people enjoying the extreme difficult of the game, but there was simply not enough payoff for me. That's kind of a shame, because Symmetry certainly has promise. Despite the lack of a really interesting story, it does some interesting environmental storytelling. The graphics have a low-poly charm, and the sound does a great job of maintaining tension even when there's not much going on. But all of that is just window dressing for an experience that asks a whole lot of players and gives almost nothing in return. The atmosphere of the game keeps making me want to go back, but I know I don't think I would find anything new on my return. Pinstripe charts a difficult course for itself. Created by solo developer Thomas Brush (you may remember his Newgrounds hit, Coma) over a five-year period, it tries to tell the tale of a father's attempt to atone for past mistakes and rescue his daughter through the medium of a combat-light puzzle platformer. It's not an impossible task, as demonstrated by similar games such as Limbo or Braid, but it requires a tightrope walker's precision to successfully balance presentation, story, and mechanics. From its opening moments, Pinstripe nails the presentation, but falls flat on its face otherwise.

The game begins promisingly, as falling snow and a lilting score fade into a scene of a father (Ted) and daughter (Bo) aboard a train car. The pair engage in some banter that should immediately endear them to most players -- not a simple task given how stilted and unnatural these relationships often come across onscreen. The paper cutout visual style is clearly inspired by the likes of Edward Gorey and Tim Burton, but it's distinct enough to stand on its own rather than just being a pastiche. Your own taste will dictate how you feel about the game's appearance, but the art is undeniably well crafted throughout. Gentle music continues playing and remarkably rich sound effects complete the picture of the journey. Making their way through the rattling train, players will quickly come across the game's antagonist and namesake, Mr. Pinstripe. Pinstripe is genuinely unsettling, projecting menace in his design, his voice, and the incredibly creepy dialogue with which he introduces himself. After solving a brief puzzle and interacting with one of Pinstripe's addictive but noxious "sacks" (don't look at me, that's what they're called), which will come into play later in the game, Ted is called to action by Bo's abduction. Players are greeted here by a gorgeous and dark landscape. The burning wreckage of a train lies strewn across the snowfield that makes up the game's first section. Snowflakes fall in the foreground, lending a serene beauty to the carnage. Elevating the atmosphere is the sparse but surprisingly moving soundtrack -- the music is great throughout, but this simple tune may be my favorite part of the entire game. A similarly lovely track accompanies the ending, which provides an unexpected bookend to the adventure. Up to this point, Pinstripe looks promising. It quickly establishes a nightmarish fairy tale world haunted by a malevolent spectre for our likable hero to overcome, and it's all presented with a grim beauty. Up to this point, players have only had presentation to rely on, and that is the game's biggest strength. But as soon as Pinstripe starts in earnest, the game's lackluster mechanics completely hamstring it. Players may have brushed aside the one quiet alarm bell of the first scene -- the simplistic and dull opening puzzle -- and assumed that it only gets better from here. Unfortunately, the gameplay never finds its footing, and players who have been even half-awake so far have already seen everything the story has to offer. Pinstripe is primarily a puzzle game, but its puzzles are uniformly unimaginative and provide nothing but a slight pause in progress. Most puzzles take the form of a series of switches to be pressed in the environment to open a gate. There are no complex sequences or tricky timings; in most cases you'll stumble across at least one switch before even finding the puzzle it belongs to. Another common puzzle is finding clues that form the combination to a lock. At one crucial juncture, you're forced to play a couple rounds of a Flappy Bird knock-off with worse collision detection, and the game even contains a couple of "Highlights" magazine-style spot-the-difference puzzles. There are a few slightly trickier puzzles to work through, but they're no more satisfying to solve. Combat, the other gameplay pillar, hardly bears mentioning. There are two types of bomb-dropping airborne enemies, which are functionally identical but with different sprites. You shoot them with a slingshot that has a simple but unsatisfying control scheme. There is one ground-based enemy that charges at you. Your talking dog companion (we'll get to it) tells you to jump on its back, so you do. This enemy shows up twice in the game. The game's only boss shows up at the very end, and it's actually a decent battle compared to the rest. It's nothing special, but it's the only encounter that requires any thought or packs any emotional resonance. So about that dog. Ted, being in Hell, is guided through most of the game by his dead dog, George. I don't know what a dog does to get sent to Hell, but that's beside the point. George is delightful. It's a clever, funny variation on Dante's Virgil, and the voice performance by musician Nathan Sharp is unerringly charming. In fact, the game's voice acting is fantastic across the board, with the highlights being the malice-dripping Mr. Pinstripe and a sort of robotic desk clerk encountered near the game's end whose voice is tinged with unnerving static and distortions. The same level of care and inventiveness goes into the sound design throughout the game, which features well done sound effects, judicious use of audio filters, and clever sound cues that help amplify the game's tense, creepy tone at key moments. This may be the first game I've ever played where the sound was undoubtedly my favorite aspect. Unfortunately, this bright spot can't make up for the game's awkward pace. Neither combat nor puzzles provide any real hurdle to the player's progress, which keeps things moving at a fast but unrewarding clip. This all grinds to a halt around two-thirds of the way through the game when, to progress to the final stage, an NPC tasks you with retracing your steps to gather a truckload of previously inaccessible pickups. This bit of exploration and puzzle solving provides probably the most significant challenge of the game, but having to trek back through old environment for a fetch quest is incredibly irritating. From this point essentially to the end of the game, my tolerance wore thin and I was ready for the ordeal to end. This harsh break in the game's flow is indicative of the way it handles narrative in general. You have a clear task to accomplish -- rescue Bo from Pinstripe -- but none of the steps you take to get there feed directly into that goal. Instead, you're jumping through whatever unrelated hoops the game chooses to put in front of you, just hoping that you'll be closer to your daughter once you do. Without a sense of escalation, the game's narrative hangs limp, allowing you to almost forget that the point of all this is to rescue a kidnapped child. Mr. Pinstripe himself even begins to undercut the game's tone as he inexplicably speaks like an angry teenage YouTube commenter, flinging sophomoric jabs like "douche" at Ted in what would otherwise be pivotal emotional encounters with his nemesis. The game's lore is revealed in a similarly halting fashion. Throughout the game, you'll stumble upon a variety of totems from Ted's past that reveal his life leading up to the events of the game. This could be a powerful narrative device, but finding these items isn't tied to the action in any satisfying way. They're mostly just lying around waiting to be picked up, and the lore revealed by these items is so readily apparent from the game's start that I wasn't sure if they were supposed to be revelations or not. Either way, they're doled out seemingly at random and land without any impact. Ted's story of guilt and redemption was supposed to be this game's selling point, but the story and the game's mechanics are so separate that they never add up to a coherent whole. One can certainly feel for the protagonist, but the game does nothing to establish his character, and everything interesting about his story happened before the game began. Within the game itself, everything is static, a redemption story without an arc. Even after writing this review, it's hard for me to pin down my feelings about Pinstripe. I don't hate it, despite the negative review, but I certainly didn't enjoy it. I found it boring and lacking in any sense of cohesion, but there are elements of it that do deserve praise. It's an original game that's trying to do and say something different, and that ought to be commended. For a one-person team, it really is quite a feat. I'll be keeping an eye on how Brush's next project, Once Upon a Coma, turns out, because there is a lot of promise in what he's made up to this point, even if it's fallen flat. And I can't overstate how much I loved the presentation. Setting aside some stiff animations, Pinstripe looks and sounds incredible. I can't recommend picking the game up, but I don't regret having sunk a few hours into it either. Pinstripe's opening and closing scenes are legitimately touching, and they've been running through my head since I finished the game. I just wish the journey between the two had been more fulfilling. |

Archives

May 2018

Categories |